I hadn’t driven a stick shift in decades. But there I was, backing our rental car down a steep road through a hilltop village, stone walls on one side, parked cars on the other, a growing line of vehicles behind me…and a delivery truck wedged between both walls blocking the way forward.

The driver tried to squeeze through a one-lane passage barely wider than our rental, let alone a box truck. It parked itself mid-village, blocking the entire road. There was no getting around it. Everyone would need to reverse their way out.

From stoops, balconies, and doorways, the town’s residents paused what they were doing to solve this real-life game of Jenga. Arms waved, fingers pointed, instructions barked.

I inched the car backward feeling for that old gas-clutch balance. At the bottom of the hill, I found enough room to stop and catch my breath. The truck passed with inches to spare (and I’m being generous using the plural here). I shifted back into first gear, eased back up the hill, and rolled past the villagers who had already returned to their daily routines.

Growing up, we lived across from my elementary school. My mom would take my brother and me to its empty parking lot in the evenings to practice driving. But the real lesson happened on the gravel hill that led up to it. She’d stop the car, a yellow Chevy Chevette, right in the middle of the incline. Set the parking brake. Switch seats.

And then she’d walk us through it: ease off the brake, balance the clutch and gas, lower the handbrake at the exact right second, and try not to stall or spin the tires. Just feel it.

That sweat-inducing moment in Filoti brought me back to those practice sessions on the hill. Muscle memory and great teaching for the win. It’s these unscripted moments that become the stories you carry home — the ones you scribble on the back of the postcard, the parts the picture on the front can’t tell.

Now, don’t get me wrong, Greece has no shortage of postcard moments — whitewashed villages, cerulean seas, epic mythology. Yet the version that stayed with me was different. It was roadside olive trees and lazy taverna lunches. It was a man watering down the dusty street in front of his seaside café. It was barking and snarling dogs chasing us on a dirt road as we pedaled past their domain.

This is Greece as I saw it. You won’t see me or my traveling companions in these photos because I am admittedly incapable of seeing snapshots when I’m given the opportunity to create something more artful. But the people I traveled with are behind every frame…and, usually, a few hundred yards ahead waiting for me.

Santorini: The Cover Shot

Santorini is widely referred to as the screen saver of Greece. You already know what it looks like: whitewashed buildings, cobalt domes, cliffs that drop into the deep. And yet, it still stops you cold when you see it for real.

We stayed at Iconic Santorini, a boutique cave hotel in Imerovigli – the balcony of the Aegean, as it is often called. As hack as it sounds, this was the kind of place that makes you whisper without realizing it or knowing why.

Santorini’s dramatic topography is shaped by fire. The crescent-shaped island forms part of a vast volcanic caldera, the result of a major eruption that happened around 1600 BCE, an event so cataclysmic, many believe it inspired the legend of Atlantis and contributed to the collapse of the Minoan civilization. Today, its volcanic past continues to shape every aspect of the island, including the unconventional methods used in local winemaking.

Forget everything you know about neat rows of vertical vines. Santorini’s vineyards grow in braided, ground-level kouloura coils untouched by phylloxera that turn each plant into a fortress against the relentless Aegean winds. The pumice-rich earth, the lasting echo of that cataclysmic eruption 3,600 years ago, acts as a reservoir, hoarding moisture from the morning mist like a sponge. It’s a centuries-old adaptation to brutal winds and sparse, volcanic soil. We sipped that history at three vineyards: Domaine Sigalas, Anhydrous Winery, and Santo Wines, the latter where we capped off our first day with a spectacular welcome-to-Greece sunset.

The next morning, while our wives checked out the island’s black sand beaches and lounged at JoJo’s Beach Bar, Tim and I took off on a mountain biking tour with Ride Greece guide and former pro cyclist Alessio Toninelli. Do you know what happens when a volcano erupts? It creates a big hole and big hills. Luckily, Alessio equipped us with electric-assist bikes that helped us climb switchbacks to the top of the island, through vineyards and forgotten villages, past crumbling chapels, windmills and sun-baked olive trees, one of the last tomato farms on the island, and down to the sea. There’s a difference between seeing a place and being in it. On a bike, you’re in it. You feel the burn of the climbs in your legs (even with the welcomed battery assist), the grit in your teeth, the smells of wild oregano in a cliffside field, the air as it changes temperature and texture.

That evening, we boarded a 42-foot catamaran with Sunset Oia for a cruise into the caldera. Departing from the port of Ammoudi, our captain shoved off to the hot springs where we jumped off into the 500 meter deep abyss. Back on board, we motored to White Beach, where we dropped anchor and enjoyed an onboard dinner of shrimp pasta, fresh sea bass, and what would become one of many daily Greek salads. Finally, anchor up, we headed for port and watched as the sun dipped below the horizon, transforming Santorini’s blue sky into a palette of pastels.

On our last day in Santorini, we hiked the Fira-to-Oia trail — five dusty miles along the caldera’s ridge. Well, sort of along the ridge. First we had to go up to get to it. And then down. And then back up again. Along the way, Jenn adorned a signpost with one of my Cousin Eddie stickers. If you do the hike, keep an eye out for it.

We ended our time on Santorini with a dinner for the ages. Our friend Joan recommended a restaurant in Oia called Lycabetus. It was once featured on the cover of National Geographic magazine, with cliffside tables jutting out high above the Aegean and the massive yachts anchored below. We scored a table and went all in on the chef’s tasting menu. Course after course that would’ve made Carmen Berzatto weep: molecular gazpacho, Wagyu tartare, truffle bonbons, and caviar…and more caviar.

Naxos: Island Time

If Santorini is the front of the postcard, Naxos is what’s written on the back. It’s the island that stayed with me long after the trip.

We reached the island by high-speed SeaJet ferry, a TGV or Eurostar on water if you will. At our villa, Milestones in Plaka, our host, Fotis, greeted us with homemade citron liqueur, sweet marinated grapes his mother made, and chilled plum rosé. It was more than a welcome gift; it reflected one of the highest virtues in Greek culture: philoxenia, the ancient tradition of hospitality, which I’m told translates as “friend to the stranger.” The word, and the practice it describes, is woven deep into Greek history, appearing as far back as Homer’s Iliad.

Fotis’s family also owned Peppermint, one of the open-air restaurants along the beach about 500 meters from the villa. Spa-like music drifted through the air. We ordered a couple pints of Mythos. The entire vibe oozed peace and calm. Tim and I nodded off while the local cat sauntered between tree branches and a lounge chair cushion. Amidst the calm, a waitress shuttled nonstop drinks from the bar down to the beach. Out on the water, novice windsurfers popped up and down on the cool blue and green water. One of Fotis’s brothers stood at the edge of the road with a hose spraying down the dirt to keep the dust down. A steady breeze blew. We ordered a few more rounds and sat watching the sea.

Somewhere in that beer and zen soaked haze I sent a quick post to social media. My friend James in the United Kingdom replied. He wanted to know if we were headed to Athens. If we were, we had to book a table at Pharaoh.

I trust James on these matters. From an intimate dinner in Chicago celebrating the anniversary of the firm he co-founded, to the annual family-style gathering at The Honey Paw in Portland, he’s Pied Piper’ed me to amazing restaurants and late night speakeasies open long after every other bar’s last call. If he says get to Pharaoh, then Pharaoh it is. I booked the table from my phone, toes pointed to the sea. Technology lets us do some pretty incredible things. Luckily for me, it’s also allowed me to make friends who live all over this amazing flying space rock we call Earth.

The next morning, things got slightly less tranquil. That’s when we took the drive I mentioned earlier, the one with the stalled truck and the sudden reminder that I hadn’t properly driven a stick shift since the Reagan administration.

Under a canopy of grapevines at Taverna Giannis in Chalki, we lunched on fire-grilled feta dosed with chili oil and tomatoes, fried Gruyère balls, and yet another Greek salad. A few doors down, I stopped to taste a homemade bougatsa at Caffe Greco, a tiny cafe tucked into one of Chalki’s quiet alleys.

Back in the car, we took a turn into the mountains, winding through hairpin roads and avoiding the occasional goat. We dropped into a small valley town that didn’t seem to have much interest in signage or exits. The only way out was the way we came in. Back up we went. I was sensing a pattern.

Back at our villa, Jenn and I hustled over to the harbor to watch the sunset. The Portara rose ahead of us, the great marble doorway that has become the emblem of Naxos. It stands on the little islet of Palatia, joined to Naxos by a narrow causeway, and is the first sight that greets travelers as the ferries arrive. The gateway was meant to be part of a grand temple to Apollo, begun in the sixth century BC under the rule of Lygdamis. His plans ended with his downfall, leaving only this solitary entrance.

As our time on Naxos came to a close, we joined Katerina of Real Wanderers Tasting Tours for an evening walk through the town. She guided us into quiet backstreets and into small shops we would never have found alone. Along the way she explained why the island is known more for its farms than its fishing: in the early centuries, fear of pirates drove people inland, and the mountains became their refuge.

We tasted olives pressed from a tree said to be six thousand years old, sampled cheeses as Katerina shared bits of history. She founded her tour company only two years ago, but her knowledge and energy made it feel like a lifetime’s work. Born on Naxos, she had studied in Athens, returned home, and stayed.

While we waited at the dock for the girls to finish shopping, the town lights flickered once and went out. Diners continued their meals, a busker kept strumming his guitar, and couples and families carried on with their Grecian passegiata along the harbor. It was one of those reminders that life on an island moves to its own rhythm.

Crete: Scale and Soul

Crete feels entirely different from Santorini and Naxos. It is a vast island with long stretches of coastline, dense vegetation, and mountains that rise sharply from the sea. Driving along the coast at sunset reminded me of the rugged beauty of northern California. After weeks of Pantone-perfect Greek island blue, it held something we had not yet seen on this trip: a cloud. Just one, but still.

We had dinner around the corner from our apartment at Steki, a lively restaurant crowded with locals. We shared a liter of white wine and another Greek salad. Tim and I order the 800g pork steak, clearly not doing the gram-to-pound conversion correctly. Nearly a pound and a half each dangled from a hook above our plates. The meal ended with the traditional dessert and a shot of raki.

It’s probably a good moment to pause and talk about raki. Every dinner on Crete ends with a glass of it. Every dinner. Raki is the island’s national drink, made from the residue of fresh grapes during the winemaking process. More than a potent alcohol, it’s a traditional symbol of friendship and hospitality. And, unlike ouzo, which we drank in copious amounts on this trip, raki is never diluted with water. It’s comparable to Italian grappa, which, I am convinced, translates directly to jet fuel.

Sunday morning I was awakened by the clanging of church bells. I’m not a religious man, but I have to admit I enjoy the community aspect of bells. I experienced something similar during a trip to Sorrento and during the calls to prayer I heard in Dubai and Abu Dhabi. I poured an espresso and sat on the veranda. A light breeze blew, chatter murmured from the street below, chants and song resonated from the altar across the street. The sounds rose slowly as the town woke up.

We grabbed breakfast at the open air restaurant below our apartment. Over coffee and eggs, we struck up a conversation with our server, Anna. In broken English and even broker Greek, we learned that she was named after her grandmother, who — according to Anna and who am I to argue — was an amazing woman not only for her age but also for her era.

Tim and Donna headed out to get their Colorado on, tackling the famous Samaria Gorge and its high vertical walls and cold stream crossings. Jenn and I were beach-bound. Or so we thought.

Getting to the beach wasn’t supposed to be hard. I mean, Greece is loaded with some of the world’s best. But Chania’s taxi scene…well, let’s just call it less-than-tourist-friendly. Not totally surprised. All the pre-trip research said local transportation was near-non-existent in Chania (and Crete in general). Taxis passed by and the drivers intentionally looked away. Yes, I checked to see if I had a booger hanging out of my nose. Eventually, we flagged one down. A nice woman named Maria who had lived on Crete for the past two decades. We tried giving our spot to an elderly local gentleman who was also waiting, but she insisted we go. Almost forced it. Not sure if that was a cultural thing, but hoping karma remembers we really did try to do the right thing. Maria dropped us off at Agii Apistoli Beach, only to find it blanketed in occupied umbrellas. We walked a half kilometer to Sunset Beach and paid our 10 Euros, grabbed a chair, and posted up. Be a traveler, not a tourist, as Tony says.

Regrouped and refreshed, we joined a personal, evening food tour led by Manos, sampling incredible young olive oils and an orange blossom honey that was to-die-for. We finished in Splantzia, Chania’s Turkish quarter, enjoying mezze and pints that pushed us beyond our limits. I love how Europeans have these streets and courtyards full of tables with people bantering about while nibbling on a constant stream of small plates and drink. Life with public squares sure beats life with parking lots.

The next morning, we woke up early, sauntered down to breakfast again at The Red Bicycle, and said goodbye to Anna. We then met up with our driver for the day, Manos (yes, another Manos, whose name, he said, was short for Emanuel from Zeus). Manos took us on an 8 hour tour of the island where we visited small towns and beaches.

Manos told us about Crete’s 3,500-year-old Vuvas olive tree — slightly younger than Naxos’s. It was fun to see the competition between the two islands for whose tree was oldest. Manos also schooled us on why Crete’s roadways are lined with oleander: The plant is poisonous to the goats that roam the island and serves as a natural fence to prevent them from wandering onto the road.

As we drove on, the road wound toward the coast, where we traded olive groves for the turquoise water of one of the world’s most iconic beaches. Elafonissi Beach is famous for its pink sand created by crushed shell fragments. Its fame preceded our arrival, however, and no umbrellas or loungers were to be found. So we waded into the water, downed a cold beer, and bailed for Falasarna Beach.

Falasarna is known for its wide, fire-hot sandy beaches, and crystal clear water. It’s the calm yin to Elafonissi’s energetic yang. We grabbed a lounge bed, ordered some food and a bottle of wine, swam a little, ordered some more wine, and spent the afternoon in relaxing bliss.

On our post-dinner walk through the old town back to the apartment, we heard music coming from an alley. People were leisurely milling about outside a jazz bar called Fagotto. We poked our heads inside to see two musicians playing on a small stage near the bar. Guitarist Adedeji Adetayo and keyboardist Asterios Papastamatakis were on fire. We grabbed a table, ordered a round of drinks, and spent the evening like locals. It was the perfect way to end the Crete leg of our trip.

Athens: The Afterimage

The alarm sounded way too early after last night’s bourbon and jazz. We hopped a 35-minute flight to Athens, leaving an island of twisty mountain roads and landing in a sprawling city with proper highways. We weren’t on island time anymore.

Athens is one of Europe’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, a sprawling metropolis with a history spanning more than 3,400 years. From atop Lycabettus Hill, where our driver Apostolis — Tolis to his friends — pulled over to let us take in the view, the city stretched wide below us, a reflection of its growth into a modern capital that weaves ancient ruins into a bustling urban landscape.

Tolis expertly shuttled us to a few of Athens’s must-see highlights, refining his comedy routine along the way. We made a quick stop at the Olympic Stadium and caught the changing of the presidential guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in front of the parliament building. The guards, with their distinctive pleated kilts, hats in red symbolizing blood, and shoes that weighed nearly five pounds each, are part of an elite light infantry unit with a history dating back to the Greek War of Independence.

We checked into our place in Psyri, which had a rooftop lounge with a clear view of the Parthenon and the Acropolis. More on that in a bit. On the walk back, we stumbled into a local bakery — bags of water and wine already throwing off my balance — and basically cleaned them out. We stuffed the bags with one of everything they made.

By the time we got back, the smell of the pastries had us thinking about dinner. We found a small restaurant called Miravilla Kitchen that had recently opened. It was situated in the opposite direction most visitors ever bother to go. The street getting there was a little rough and tumble, but when we turned the corner, the whole mood shifted. Neighborhood energy. Laughter. And a rooster dish to die for.

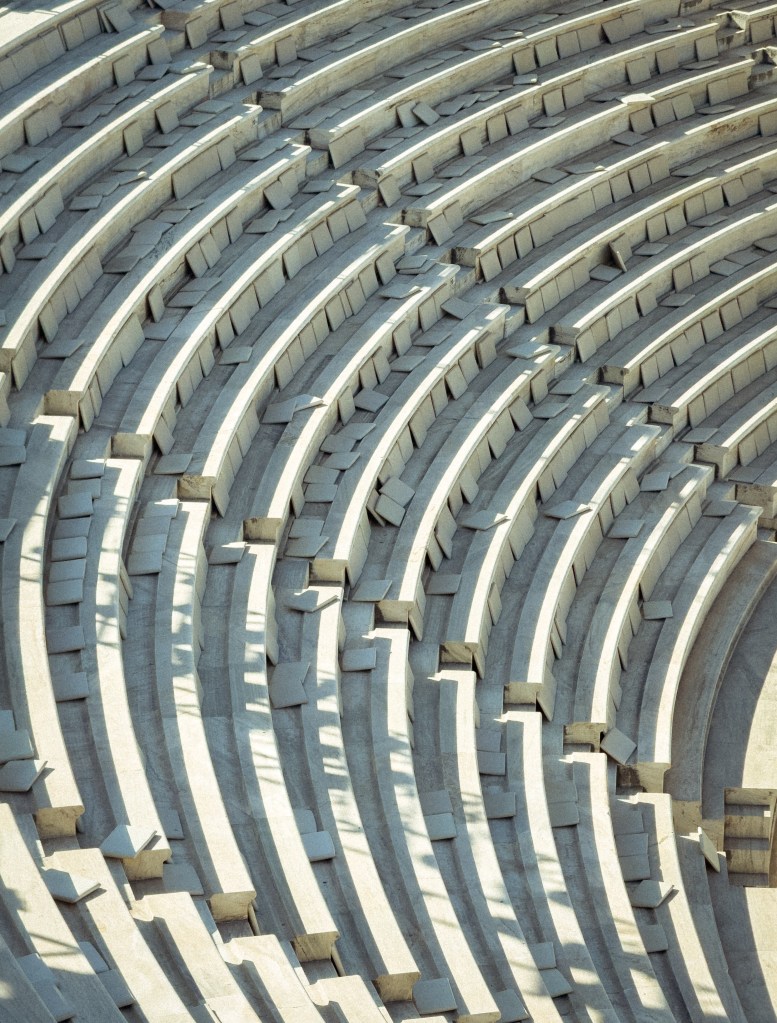

The next morning, we did what anyone visiting Greece is required to do: toured the Acropolis. The walk up wound past scattered columns and marble fragments, reminders that Athens is as much an ongoing excavation as it is a modern city. Our guide, a teacher on summer break (and still very much in teacher mode), filled the climb with a semester’s worth of history.

The hill itself is shot through with quartz, she said. Great for ancient builders, not so great for modern cell service. The Greeks were engineers and mathematicians as much as artists, and nowhere is that clearer than at the top.

The Parthenon, the central temple on the Acropolis, was constructed between 447 and 432 BCE during Athens’ Golden Age under Pericles and dedicated to Athena. Its structure exemplifies the sophisticated abilities of the Greek builders. To achieve a level of divine perfection worthy of their patron goddess, architects employed complex optical refinements: the base rises, columns exhibit a subtle swell, and every column leans slightly inward. These precise, costly adjustments were designed to counteract human visual distortion, acting as a powerful declaration of Athens’ wealth, genius, and supreme devotion to Athena.

After hours of sun, stone, and centuries of context, we decided we’d earned something a little different: a catamaran sunset cruise along the Athenian coast.

The next day, we wandered through art galleries in Kolonaki, a neighborhood that feels equal parts culture and couture. We stopped for an impromptu — and far more elegant than we probably deserved — cocktail at the King George Hotel, a 19th-century landmark once built as an annex to the Greek palace.

Afterward, I roamed solo for a while. Just wandered. That’s usually when I find my favorite images. I stumbled onto a covered market shaped like a cross or maybe a crossroads. Butchers and fishmongers were busy calling, chopping, and carving.

Later, I parked myself at a table in the square a few blocks from our apartment and ordered a Mythos. Sitting there, I practiced one phrase: “Éna akóma kai patát” — one more Mythos and fries.

Okay, maybe it was more than one more. My flâneur mode was fully engaged. Third places are essential. You feel it everywhere in Europe — cafés, squares, stoops — and you realize how much America gave up when it chose cars over conversation.

The Real Magic

On our last night in Greece, we finally made it to Pharaoh, the restaurant James had messaged me about back in Naxos (followed by craft cocktails at The Clumsies). The four of us sat at a small table, the city easing into evening outside. The meal was exactly the right capstone to our time in Greece.

Somewhere between courses and bottles of wine, it struck me that James’ message was more than a recommendation, it was proof of the real magic of travel. The world, it turns out, is smaller than we think. The more you see, taste, and hear, the closer everything feels. Different languages, foods, and landscapes, but a shared connection underneath it all. The best parts — the ones that stay with you — are the moments you share with the people closest to you, wherever you happen to be.