Not every idea deserves to live. But plenty of good ones die before they get a chance. They vanish under the weight of calendars, inboxes, and interruptions — the thousand small frictions that erase a thought before it has time to become something real.

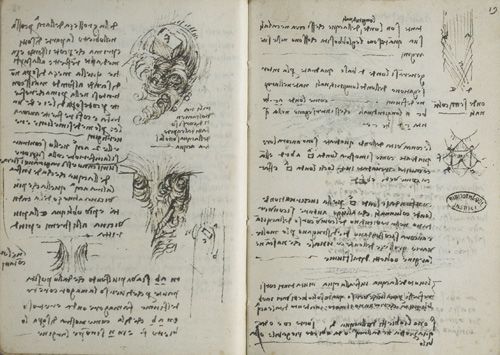

Leonardo da Vinci lived this problem as fully as anyone we remember. His notebooks are filled with flashes of brilliance that never moved an inch toward becoming real. They reveal a mind where ideas arrived faster than execution, and a compulsion to record them, even when they might never be completed. They stayed ink on paper. Imagine if he’d had something to carry those sparks just a little further.

Today, we do.

AI gives us the inch Leonardo never had: not just a way to keep an idea alive, but a way to work it before it’s fully formed. A sentence can be pushed, expanded, challenged. A paragraph can be reshaped or broken apart. A rough draft becomes something you can interrogate. All of it quickly enough to learn whether there’s anything there worth shaping at all.

But that inch isn’t enough.

Ideas still need something only humans provide: judgment.

I learned this early in my career working with Mike Zisman and Larry Prusak on IBM’s knowledge management business (well, they worked on it; I helped them communicate it). Much of that work, as I remember it, centered on the difference and interplay between explicit and implicit knowledge. What you can write down versus what you simply know. Facts versus instinct.

AI is extraordinary at the explicit. It can generate variations, surface patterns, and produce options at scale. But it can’t do the tacit work. It can’t feel the off-note in a promising idea or sense when something ordinary is pointing to something deeper. It can generate possibilities, but it can’t tell the signal from the static or decide which ones matter.

AI raises the premium on expertise. When ideas become cheap and abundant, discernment becomes scarce. The advantage shifts to people who can interpret what AI produces with context. They implicitly know when to push an idea further, when to reshape it, and when to let it go.

That shift changes what expertise actually looks like. It’s no longer defined by how many ideas you can generate, but by how well you can tell which ones hold up under pressure. When beginnings are cheap, judgment is knowing which ones are worth the effort.

This is the consequence of getting the inch Leonardo never had. AI widens the funnel of possibility, but it doesn’t make sense of what flows through it. It accelerates ideas without considering what happens when they meet reality.

That responsibility now belongs to us.

AI can extend a thought, multiply it, and push it forward faster than ever before. But it can’t decide what matters. That decision is what turns an inch into something real.